Designing Urban Wildlife Habitat

It might be said simply that we all owned our cities, as the whole civilization history told us that humanity is the one that creates and develops cities across times, especially, now, in the era of technological advancement which will make a great shift on urban living ever than before. However, the current global environmental crisis has warned us to rethink city development and that we should be more concerned with ecological factors – natural resources and urban wildlife. Birds, insects and squirrels, dwelling on the trees and running along the electricity post, can help enhance urban ecology to become more complete and sustained.

If we developed the city only with humanism point of view, constructing buildings, roads and bridges without environmental and contextual concerns, the existing living species will undeniably be affected from habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, light and noise pollution, and even chemical runoff pollution. This also leads to the coming of invasive species to urban areas, disturbing the ecology to greatly adapt to unavoidable changes, and as a result affect our urban living once again. Hence, this is why Homosapiens should take responsibility to create cities and blend our lives with urban wildlife.

Urban Wildlife Habitat Agenda

There are potentially 2 approaches on designing urban wildlife habitat. The first one is “Preservation,” meaning to preserve original habitat without any disturbance or destruction, in order to exist sustainably. Second, “Restoration” should be considered to increase and regain the amount of habitats, by revitalizing their structure and function.

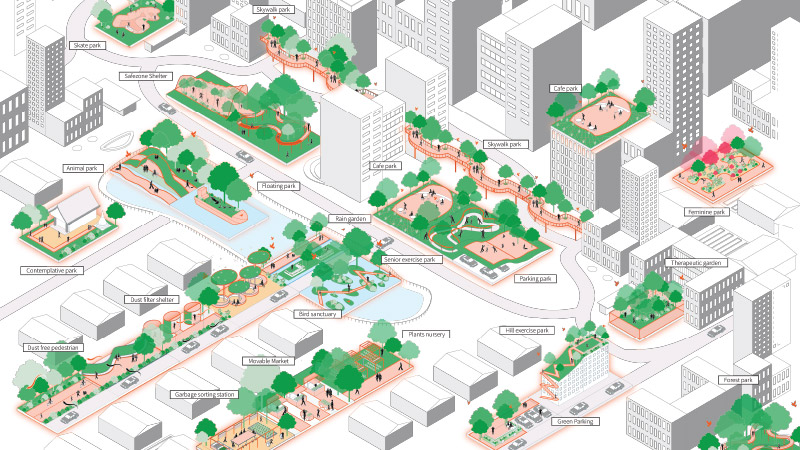

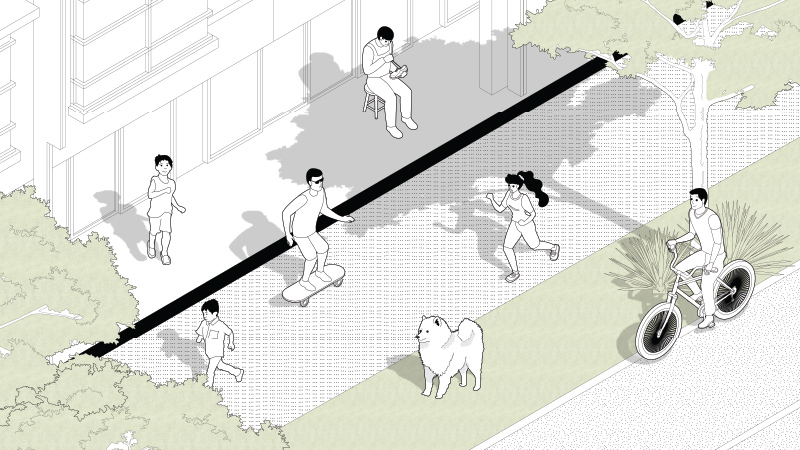

We might simply start to understand by studying how physical structure and function of the ecosystem are related with urban areas as a way of finding for human and urban wildlife coexistence. Patches and Corridors should be incorporated within the city as animals’ territories and commuting routes between urban and rural areas. We might also need to define the usage intensity of each area – whether it is a hard or soft boundary, and if it is for only animals, humans, or both.

Urban Wildlife Habitat Design Strategy

Since the city’s ecology should be both well-preserved and restored at the same time, the existing natural areas that have potential to develop into urban wildlife habitat, need to be revitalized and organized effectively as well. This restoring method is like building up a new ecosystem, meaning we need to clearly understand the site and design goal on achieving places for wildlife through 4 design strategies and analysis – Urban wildlife types, living factors, site location, and community engagement.

Design Strategy 1 : Urban Wildlife Types

There are 3 urban wildlife types :

1 Avoider : (e.g. Fishing cat, Mongoose) They often are large/predator species, the last ones of the food chain which are discouraged by humans and cannot tolerate fragmented habitat. They normally reside in undisturbed land or natural reserves with large territory range.

2 Adapter : (e.g. Tree sparrow, Zebra dove, Bat) They often are small to medium native species, living in both undisturbed land and urban fringe with humans. They find foods in small or shifting territory ranges, and can take advantage of human food and shelter sources.

3 Exploiter : (e.g. Common pigeon) They often are species that migrate for various transient ranges and are commonly found in urban areas. Some of them also depend on human food and shelter sources.

Design Strategy 2 : Urban Wildlife Living Factors

Similar to human primary factors – house, clothes, food and medicine, urban wildlife has 4 essential living factors as well, including food resource like trees for birds and insects, water for drinking and bathing, nestling place like trees, ponds, and wood piles, and the last one, cover or shelter for hiding like bushes, tall grasses, mounds and deep swamp. All of the aspects depend on each species, so during analysing methods, we have to study each case more in detail.

Design Strategy 3 : Site Location

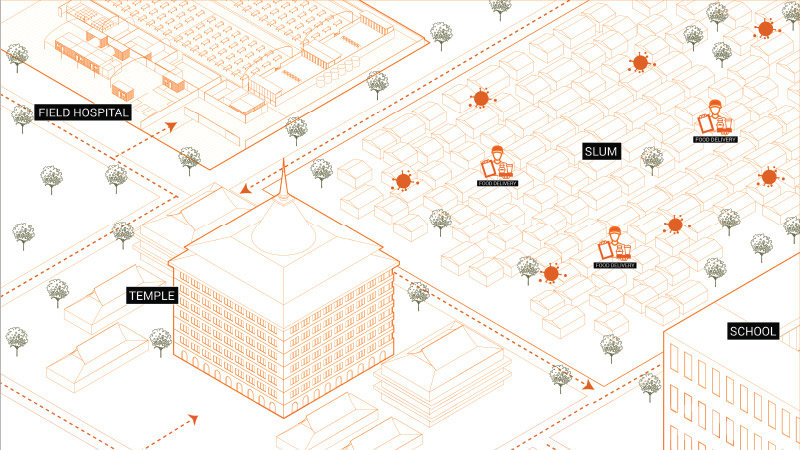

Site analysis is another critical process and can be done by studying the relationship between the site and surrounding context. Their connection are really important because the animals can commute on land and through air by rows of trees and waterways between each green space.

Design Strategy 4 : Community Participation

Designers and developers should inform people living nearby the site about urban wildlife and their ecological benefits, in order to live well together with sympathetic understanding, not disturbing the animals’ habitat.

Design

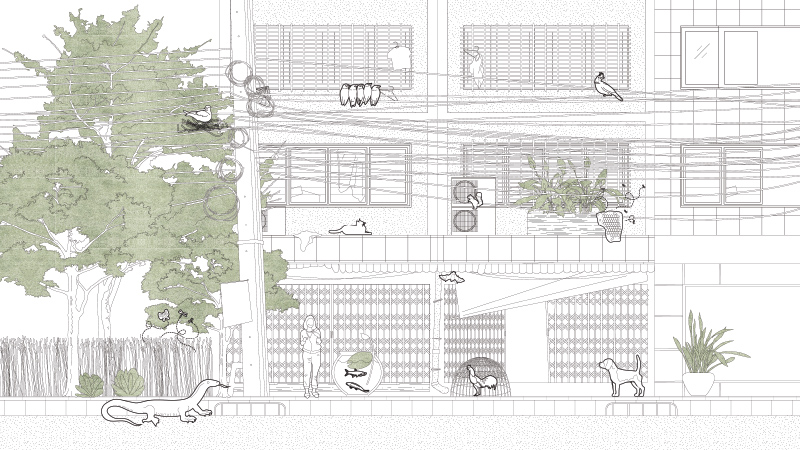

Adapting those strategies to design a real habitat, we might start from looking at the four factors compared with existing urban infrastructure like lighting and building to see how they possibly impact the upcoming habitat. Hence, natural elements can be rearranged to create animal shelters such as logs and stone piles in water for fishes and frogs. Likewise, growing trees with various heights on land can cover a great range of urban wildlife such as emergent layer for hawks and eagles, canopy layer for owls and kingfishers, and ground layers for sparrows, as well as on-land shelter that is big and dense enough like bushes and shrubs for bird to hide from domestic cats.

For food resources, plants that offer food in all seasons should be grown, especially during late dry season and mid rainy season where birds are laying their eggs. We also need plants that are pollinator resources, resulting in palettes of food resources that consist of both plants and insects. In any case, animal-based territories should be focused on growing local species in order to allow ecological succession, while human accessible areas can simply start from growing aesthetically.

Looking in the long term, this kind of urban revitalization concerning ecology and wildlife is a part of building green infrastructure – green area and water channels, since the space can accommodate various species, manage run-off water, flow water into underground level, maintain soil quality and at the end, incubate sustainability and resilience for the city.

Mori Haus

Mori Haus offers an essence of relaxing and reconnection with nature as a condominium located within the crowded neighborhood of Bangkok. The landscape is designed with the main concept of “Zalley,” arranging enclosed residential buildings as mountains around a cozy private garden space. Here, a variety of plants are selected to imitate a forest ecology and serve specific functions – facade plants for screen buffering, aromatic plants for ornamentation, and of course, animal attractive plants and flowers for maintaining biodiversity.

Jin Wellbeing County

Jin Wellbeing County is the first senior oriented mixed use development in Thailand, comprising residence, commercial unit and hospital, with 35 Rai of completion in Phase I. Our landscape design is featured with a perfect harmony with nature which enhances people’s physical and mental health. A combination of functional water management systems and forest-imitated plants selections become a food source and habitat for urban wildlife such as birds, fishes, insects and squirrels regenerating a resilient ecosystem at the end.

Reference:

Cecil, K. (n.d.). Urban Wildlife: Challenges and Opportunities. Retrieved from https://web.extension.illinois.edu/lcr/wildlife.cfm

Felson, A. J. (2013). The Role of Designers in Creating Wildlife Habitat in the Built Environment. In Designing Wildlife Habitats (pp. 215–277). http://doi.org/10.3368/er.33.2.223

Handel, S. N. (2013). Ecological Restoration Foundations to Designing Habitats in Urban Areas. In Designing Wildlife Habitats (pp. 169–186).

Joshua, F. (2016). the Yardworks Project : Developing Urban Ecological Design Strategies for Residential Private Property. Landscape Research Record, 5(5), 89–100.

Mohamad, N. H. N., Idilfitri, S., & Thani, S. K. S. O. (2013). Biodiversity by Design: The attributes of ornamental plants in urban forest parks. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 105, 823–839. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.11.085

Moxon, S. (2019). Designing for Wild Life : Enabling City Dwellers to Cohabit with Nature. International Association of Societies of Design Research Conference 2019.

Stokes, M., & Chitrakar, R. M. (2012). Designing “other” citizens into the city : Investigating perceptions of architectural opportunities for wildlife habitat in the Brisbane CBD. In QUThinking Conference: Research and Ideas for the Built Environment.

The Urban Wildlife Working Group. (2012). What is Urban Wildlife? Retrieved from http://urbanwildlifegroup.org/urban-wildlife-information

มงคล ไชยภักดี, & วัลยา ไชยภักดี. (2552). แนวทางในการป้องกันการรบกวนจากนกพิราบ. ผลงานวิจัยและรายงานความก้าวหน้างานวิจัย ประจำปี 2551, 185–194.